“If it is a devil you seek, then it is a devil you shall have!”

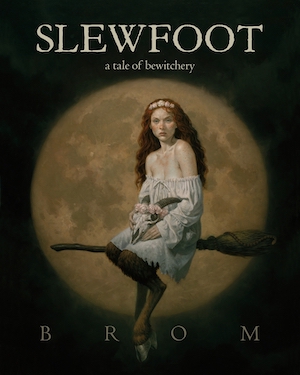

Set in Colonial New England, Slewfoot is a tale of magic and mystery, of triumph and terror as only dark fantasist Brom can tell it. We’re thrilled to share an excerpt below, along with an exclusive peek at one of Brom’s haunting illustrations! Slewfoot arrives September 14th from Nightfire.

Connecticut, 1666.

An ancient spirit awakens in a dark wood. The wildfolk call him Father, slayer, protector.

The colonists call him Slewfoot, demon, devil.

To Abitha, a recently widowed outcast, alone and vulnerable in her pious village, he is the only one she can turn to for help.

Together, they ignite a battle between pagan and Puritan—one that threatens to destroy the entire village, leaving nothing but ashes and bloodshed in their wake.

Wake.

No.

They are here. You must kill them.

Who?

The people… smell them.

The beast did, smelled the blood beating in their veins. There were two of them. It opened its eyes.

You must kill them, Father.

Father?

Do you remember your name?

The beast considered. “I believe I have many names?”

Many indeed.

“Who are you?”

Your children. You must protect us, protect Pawpaw… from the people. Do not fail us. Not again.

“I am tired.”

You need more blood.

The goat beast heard a thump from far up above, realized he could not only hear the people, but feel them, their souls. One was a man, the other a woman. The man was at the opening now.

We will call them, bring them to you. You can do the rest. It is time to feast.

“Yes, time to feast.”

“That’s close enough,” Abitha said.

Edward ignored her, walking up to the mouth of the cave, his ax slung over his shoulder.

“Edward, you will fall in.”

“Goodness, woman. Stop fretting so. I am not going to fall in.”

“Stop!” Her voice suddenly severe. “It… it’s in there, Edward.” He met her eyes.

“I know you will think me silly, but… well, I felt something in there. I truly did.”

“What do you mean?”

“The Devil!” she blurted out. “I can feel it!”

Buy the Book

Slewfoot

“The Devil?” He smirked. “The very Devil? Here in our woods. I shall alert Reverend Carter right away.”

“It is not a jest!” Her color was up, and it made him grin.

“Abitha, do you think old Slewfoot is going to grab me and carry me down into his pit?” By the look on her face, he could plainly see that she did.

“You think it funny?” She clapped her hands to her hips. “Well, you can just throw yourself in then, save me and Slewfoot the trouble. See how I care.”

And he did see how she cared, and he could see she cared a lot. He stifled his grin. “Ah, Abitha, I am sorry. I do not mean to mock you. I will be careful. I promise.” This seemed to placate her somewhat. But her eyes kept darting back to the cave, and he wondered just what it was she’d seen or thought she’d seen. Whatever it was, she wanted him to build a gate across the entrance. She’d said it was to keep any more livestock from wandering in, but he was now pretty sure it was to keep whatever she thought was in there from getting out.

Loud squawks came from overhead. Abitha started. They both looked up. “Trumpeter swans,” he said. “They’re coming home.”

Abitha pushed back her bonnet to watch the birds and several long locks of her hair fell loose, the rich auburn color lit up by the spots of sunlight dancing through the trees. What a picture you make, Edward thought. Wallace had quipped about her looks, about her freckles and scrawny figure. And perhaps she did lack the darling cheeks and dimples of Rebecca Chilton, or the shapeliness of Mary Dibble, yet to Edward, Abitha’s striking green eyes seemed to radiate more life and loveliness than both of those young women together.

“Spring is almost upon us,” he said. “We can start planting soon.”

She flashed him an almost vicious smile and he understood everything about that smile. “And, God willing, we will be done with him soon,” she spat. “Wallace will have to find someone else to lord over. Glory, but what a wondrous day that will be. Will it not?”

“It will.”

She stepped closer, reaching for his hand. He took hers, gave it a squeeze, but when he went to let go, she held on, pulling him close and slipping an arm around his waist, pressing her stomach against him. Edward tensed as thoughts of their lustful night returned. He blushed and drew back, suddenly unable to meet her eyes.

“What is it, Edward?”

“You know we should not act in such a way. The flesh makes us weak. About last night, I overstepped. I am ashamed.”

She twisted loose from his hand, and the look on her face, it was as though he’d slapped her.

See, he thought, such shameful lust only leads to pain. I will destroy that drawing, all the drawings. Lord, forgive me, I was so weak.

She walked away from him, over to the cave. He could see by the set of her shoulders that she was upset. She pulled something from her apron, hung it in front of the cave. Edward stepped up for a closer look, saw that it was a cross made from twigs and feathers, bound in red yarn.

“What is that?”

“But a warding charm. Something my mother used to keep wicked spirits at bay.”

He looked quickly around. “Abitha, you must not. What if someone sees?”

“None are out here but us.”

“No more of these spells of yours. Do you hear me. It must stop.” He realized the words had come out harsher than he meant.

“It is but rowan twigs and twine, Edward. How—”

“Twigs and twine that will see you tied to the whipping post!”

“Edward, you well know that several of the women make charms; they are considered nothing more than blessings.” And this was indeed true, also true that home remedies, potions, and cunning crafts were used when folks could get their hands on them, surreptitiously of course, but it was common practice to be sure.

“That”—he pointed at the twigs—“is no simple blessing. Now you must promise to stop with your spells and charms.”

“How is it that we had biscuits this morning, Edward? Your brother has saddled us with such a burden that it is only through my bartering these very spells and charms that we have flour and salt this day.”

“Yes,” he stammered. “Well, we will have to make do. It must stop as of today. It is just too risky.”

“I am cautious.”

“There is no hiding what we do from God. He will see us and he will punish us accordingly!”

“Why are you acting so, Edward? Is this about last night? You must quit this belief that God will punish you for seeking a bit of pleasure, for trying to find some joy in this harsh cold world.”

“For once just do as I bid. No more spells, Abitha. Swear to me!”

“You sound like my father. Must I swear off every pleasure in life? I am sick to death of this want to suffer needlessly. Suffering does not bring one closer to God.” She plucked up the cross. “I was only trying to protect you from whatever wickedness lies within that cave. But if you prefer to have it come crawling out after you, then that is just fine with me!” She gave the cave one last fretful look, then stomped off.

Edward watched her march away, disappearing into the trees. Why must everything I say come out wrong? he thought. Abitha, I could not bear it should anything happen to you, that is all I am trying to say. I cannot be alone not again.

Edward let out a long sigh and began sizing up the nearest trees to build the gate from. He noticed how rich the soil was in this area, thought what good farmland it would make once it was all cleared.

A low moan drifted from the cave.

Edward spun, ax raised. He waited—nothing, no bear, no devil. He lowered the ax. You’re hearing things. But he’d more than heard that peculiar sound, he’d felt it, he was sure, like something had touched him. She’s done spooked you, that’s all. All Abi’s talk of devils has put devils in your head.

He glanced back toward the cabin, hoping to see Abitha, but he was alone. He realized that the sun was gone, hidden behind thick clouds, and suddenly the forest seemed to be closing in, as though the very trees were edging toward him.

Another sound, this time more of a cry, a bleat maybe.

Samson? Of course. He almost laughed. The goat. What else could it be?

He stepped up to the cave, trying to see inside. The sound came again, faint, from somewhere deep within. He removed his hat and slid into the cavern, carefully prodding the floor with the ax, testing for drops. As his eyes slowly adjusted, he scanned the gloom, found only scattered leaves and a few sticks. There was a smell in the air, more than the damp leaves. He knew that smell, he’d slaughtered enough farm animals in his time—it was blood.

Another bleat; it seemed to come from the far shadows.

“Samson,” he called, and slid deeper into the gloom, crouching as not to hit his head on the low ceiling, squinting into the darkness. It’s no good, he thought. I need a lantern. He started back, then heard another sound, a whimper. A child? He shook his head. Nay, just echoes playing tricks. He continued out toward the entrance.

It came again, a sort of eerie sobbing. The hair on his arms prickled as the unnatural sound crawled into his head. I should leave, he thought. The sobbing turned into mumbling; someone was speaking to him. He didn’t understand the words, then he did.

“Help me… please.”

Edward froze. The words were those of a child, but they sounded hollow and he wasn’t sure if he was actually hearing them or if they were in his mind. “Hello,” Edward called. “Who’s there?”

“Help me.”

“Hold on, I will get rope and a lantern. Just wait.”

“I’m scared.”

“Just hold on, I shall be right back.”

“I cannot, cannot hold on. I’m slipping!”

Edward hesitated—the voice, so strange, almost not human. But what else could it be?

“Help me!”

That had not been in his mind. He was certain.

“Help me!”

He saw a small face appear far back in the shadows, that of a child, a boy perhaps, almost glowing, some illusion of the light making him appear to float in the darkness like some disembodied head.

“Help me! Please!”

Edward swallowed loudly and began crawling toward the child as quickly as he dared, sliding on his knees, prodding the cave floor with the ax. He entered a smaller chamber, this one pitch. He grasped for the child, but the child flittered just out of reach. And it was then that Edward saw that the thing before him wasn’t a child at all, but… But what—a fish? A fish with the face of a child?

Edward let out a cry, yanking his hand back.

The child giggled, smiled, exposing rows of tiny sharp teeth. Edward saw that the thing’s flesh was smoky and all but translucent. He could see its bones!

“Oh, God! Oh, Jesus!”

Something touched the nape of Edward’s neck. He jumped and spun around. Another face, there, right before his own. Another child, but not, its eyes but two sunken orbs of blackness. It opened its mouth and screamed. Edward screamed; they were all screaming.

Edward leapt up, ramming his head into the low ceiling with a blinding thud. And then he was falling—sliding and falling, clawing at the darkness. He slammed into rocks, searing pain, again and again as he crashed off the walls of a shaft, and then finally, after forever, the falling stopped.

Edward opened his eyes. His face hurt, his head thundered, but he could feel nothing below his neck, knew this to be a blessing, knew his body must be a twisted and mangled mess. He let out a groan.

All should’ve been pitch, but the thick air held a slight luminescence and he made out rocks and boulders and bones. The ground was nothing but bones.

Where am I? But he knew. I am in Hell.

Then he saw it—the Devil, Lucifer himself. The beast sat upon its haunches, staring at him, its eyes two smoldering slits of silver light. Those simmering eyes pierced his soul, seeing all his shame, all the times he’d sinned, all the times he’d lied to his father, the times he’d profaned God’s name, the books, those evil books he’d bought in Hartford, and most of all his lustful drawings, the ones he’d done of Abitha. “God, please forgive me,” he whispered, but he knew God wouldn’t, that God had forsaken him.

The ghostly beasts with the faces of children fluttered down, giggling as they circled him, but Edward barely noticed, his terrified, bulging eyes locked on the Devil.

The Devil clumped over to Edward.

Edward tried to rise, tried to crawl away, but couldn’t do anything more than quiver and blink away the tears.

The beast shoved its muzzle against Edward’s face. Edward could feel the heat of its breath as it sniffed his flesh, the wetness as it licked his cheek, his throat. Then a sharp jab of pain as the beast bit into his neck.

Edward stared upward, at the sliver of light far, far above, listening as the Devil lapped up his blood. The world began to dim. I am damned, he thought, and slowly, so slowly, faded away.

“Edward!” a woman called from above. “Edward!” she cried.

Edward didn’t hear it. Edward was beyond such things, but the beast heard.

The other one, Father. Quick, now is our chance.

The beast shook his shaggy head. His belly full, he wanted only to close his eyes and enjoy the warmth spreading through his veins. “Tonight,” he mumbled, barely able to form the words. The beast raised its front hoof and watched as the hoof sprouted a hand, one that sprouted long spindly fingers, which in turn sprouted long sharp claws. “I will kill her tonight.” The blood took him and it was as though he were floating as he drifted slowly off into a deep slumber.

Tonight then, the children said.

Wallace trotted slowly along on his stallion toward Edward’s farm. Going over and over what he must say, wondering how he’d been reduced to this, to pleading with Edward to accept Lord Mansfield’s offer.

I did everything right, Papa. You know it true. Edward and me should be working together, as you always wanted. Building our own tobacco empire… just like the plantations down in Virginia. Instead I am the fool of Sutton who knew naught about tobacco. Cannot go anywhere without seeing it on their faces. He spat. No one but you, Papa, saw me working my hands to the very bone trying to save that crop, picking off worms day after day, even by torchlight. Is it right, I ask you, that I should now have to grovel before Edward and his harpy of a wife? Is it?

Wallace reined up his horse at the top of the hill above Edward’s farm, his stomach in a knot. And you know the worst part of it, Papa? It will be seeing her gloat as I beg. I know not if I can bear it. Why does that woman despise me so? Why must she vex me at every turn? I have been generous, have done my best to welcome her into the fold.

Wallace heard a shout. Turned to see Abitha, Thomas Parker, his brother John and two of their boys, all heading toward him at a rapid clip. John was carrying a long loop of rope and a couple of lanterns.

“Wallace,” John cried. “Come, quick. It is Edward. He has fallen into a pit!”

“A pit?” Wallace asked. “What do you mean?”

“Just come,” John called as they raced by.

Wallace followed them down into the woods below the field.

“There,” Abitha said, pointing to a cave opening tucked between some boulders.

Wallace took a lantern and peered into the cave. “Edward,” he called. “Edward, are you there?”

“Anything?” Thomas asked.

Wallace shook his head. “Naught but sticks and leaves.”

“In the back,” Abitha said, her voice rising. “The pit is in the back. I tell you he’s fallen in. I know it. Please, you must hurry!”

Wallace glanced at the brothers, Thomas and John. When Abitha couldn’t find Edward, she’d gone over to the Parker farm seeking help, but neither of these men appeared in any hurry to enter the cave.

Abitha snatched a lantern from John and headed for the entrance, but John grabbed her, held her. “Hold there, Abitha. If there’s one pit, there may be more.

We must be cautious.”

“We have no time to be cautious.”

Wallace spied Edward’s hat in the leaves. He picked it up and handed it to Abitha. It took the wind out of her and she stopped struggling.

“Here,” Wallace said, passing his lantern to Thomas. Thomas had brought along their longest rope, and Wallace took it from him. He unfurled the rope, tying one end around a boulder. He tested the rope, nodded to John. “Keep her out here.” He then slid into the cave, followed a moment later by Thomas and his eldest boy, Luke.

Luke and Thomas both held a lantern, allowing Wallace to lead while keeping his hands securely on the rope. He tested the ground with his forward foot as he went, ducking his head to avoid the low ceiling. With the light he could now clearly see that the dirt and leaves had been kicked up. The tracks led them to a smaller chamber at the rear of the cave. Wallace hesitated; he felt a chill, not that of cold, but a wave of foreboding that he couldn’t explain.

The men brought the lanterns forward, revealing a pit of about six feet circumference. Wallace spotted an ax by the pit. He tested the rope yet again, then moved into the chamber. After a moment, all three of them were peering down into the chasm. And again, that deeply unsettling chill ran through him; it were as though the very darkness was staring up at him.

There came a commotion behind them and Wallace turned to find Abitha looking over Thomas’s shoulder, her eyes full of dread.

“Do you see him?” Abitha asked in a hushed, desperate tone. “Anything?”

“You are to leave at once,” Wallace said, but knew he was wasting his breath.

“There,” Thomas said, pointing. “Is that Edward’s?”

A shoe sat against the wall of the cave. Abitha pushed closer. Thomas grabbed her, trying to keep her from getting too close to the pit. “Edward!” she cried, her voice echoing down the dark chasm.

Luke crouched, held the lantern out, and squinted. “And that, there. What is that?”

Something white gleamed back at them from a rock jutting just below the lip of the pit. Wallace knelt for a closer look. Oh, good Lord, he thought. A tooth, a human tooth.

Abitha let out a groan. “Oh no, Edward. No.” She slid to her knees. They were all looking at the pit now the way one looks at a grave. “Someone will have to go down,” Abitha said.

Wallace tossed a small stone into the pit. They listened to the ticktack of the stone bouncing down the shaft. On and on and on it went, never really stopping, just fading away. They looked at one another, all knowing what that meant.

“We cannot leave him down there,” she said. “What if he still lives?”

“It is too deep… too treacherous,” Wallace put in, but what he didn’t add was that no force on earth could compel him to go down into that pit. That every bit of him felt sure there was something foul and malevolent waiting below. “We cannot risk more lives.”

“Well, if you will not then I will.”

“Abitha,” Thomas said gently. “There will be no going down. No rope is so long.”

“Mayhap he is not at the bottom, but upon some ledge.”

“Abitha, please,” Thomas said, holding the lantern out over the pit. “Look down. Truly see.” He held her arm tightly so she could peer over the lip, her eyes searching desperately.

“Edward!” she called, and they all stood there as the echo of her husband’s name died out, straining their ears for a reply, a groan, a gasp, a cry, anything, but heard only their own breathing.

And Wallace saw it on her face then, as she stared at the tooth, that she knew the truth of it, that there’d be no surviving such a fall.

Screaming.

Flames licking a night sky. Huts on fire. People running in all directions, their faces fraught with terror. Bodies, so many bodies, limbs torn

away, guts ripped open, brains splattered. The air smelling of blood and burning flesh. And the screams, going on and on as though never to stop.

The beast opened his eyes.

“At last, Father. You’re awake.”

The beast groaned. An opossum stood before him on its hind legs, thin to the point of emaciation, its face that of a human child, a boy perhaps. Its two eyes, small and black, with tiny pinpricks of light at their centers, sputtering like fireflies.

“Who are you?” the beast asked.

“He is awake,” the opossum called, his voice echoing up the shaft.

A large raven flew silently into the room, alighting on a rock, followed by a fish. The fish floated in the air, swishing its tail softly back and forth as though holding itself in place against a gentle current. They too had the faces of children, the raven with human hands instead of claws, the flesh blue as the sky.

“Get up, Father,” the opossum said. “There is blood to spill.”

“Who are you?”

“Have you forgotten us?” The beast shrugged.

The opossum appeared deeply disturbed by this. “You have known us for a long time. Try now to remember. It is important.”

The beast tried to remember, to recall anything, but his mind seemed nothing but tumbling shadows and hollow echoes.

The opossum clutched the beast’s hand. “Close your eyes. See us!”

The beast closed his eyes, felt a soft pulse coming from the opossum. The pulse fell in rhythm with his heartbeat and hazy shapes began to appear. Slowly they came into focus and he saw them, little impish beasts just like these, hundreds of them, running through a forest, chanting and howling, their childish faces full of fervor and savagery. He tried to see more, but the vision blurred, began to slip away, then nothing.

The beast let out a frustrated groan, shook his head, and opened his eyes. The small creatures shared a worried look.

“Do not fret,” the opossum said. “It will all come to you soon. You just need more blood. We are the wildfolk… your children.” The opossum thumped his own chest. “I am Forest.” He pointed to the raven—“Sky”—then the fish—“Creek.”

“And I am Father?”

“Yes,” Forest said. “You are the slayer… our guardian. It is time to leave this pit. Time to drive the people away before they kill Pawpaw.”

“Pawpaw?” The name brought forth an image, a shimmering mirage, that of a giant tree with crimson leaves. “Yes, I know this.”

The children grinned, revealing tiny needlelike teeth. “Hurry,” Forest called. “Follow us!”

Excerpted from Slewfoot, copyright © 2021 by Brom.

This excerpt appeared earlier on Tor.com in July 2021.

Buy the Book

Slewfoot